LABOR is pleased to present Ottagono, a solo show by the Canadian artist, Terence Gower.

Gower (1965) is best known for work that deals with architecture, specifically his investigation of the accumulated meanings of the architectural form. For example, in postwar Mexico, he determined the clean geometry of modern buildings expressed the cultural sophistication of the elite. At the same time, this geometry represented utility and social progress to the government that built the post-revolutionary public infrastructure. Gower’s videos, Ciudad Moderna (2004) and Polytechnic (2005), each show one of these distinct meanings of modern architecture in Mexico.

In the body of work that comprises his new exhibition at LABOR, the artist extends this investigation into the realm of abstract art.

A visit to Ottagono starts with the viewing of the video New Utopias (2010). Gower mines the world of entertainment (in this case popular films and concert footage of the 1970s) in a search for forms that contain broader cultural significance. Gower, acting as the presenter, shows how a series of solid geometric forms—geodesic domes, conical spacecraft— represent the utopian aspirations of the society of the period. The work shown in the main gallery applies the representational system of New Utopias to the world of postwar abstraction.

With the piece Noguchi Galaxy (2012) –made of sculptural fragments- as the central source of gravity of the show, Ottagono is a map of the sculptural unconscious. After a brief career as a Mexican social realist, Isamu Noguchi returned to his country and to abstract creation in a search for new forms of social engagement. The result is a series of utilitarian objects, like the now-ubiquitous Noguchi table, with its forms extracted from the sculptor’s vast visual alphabet of flat graphic forms; Some of them have found their way into Gower’s hanging sculpture.

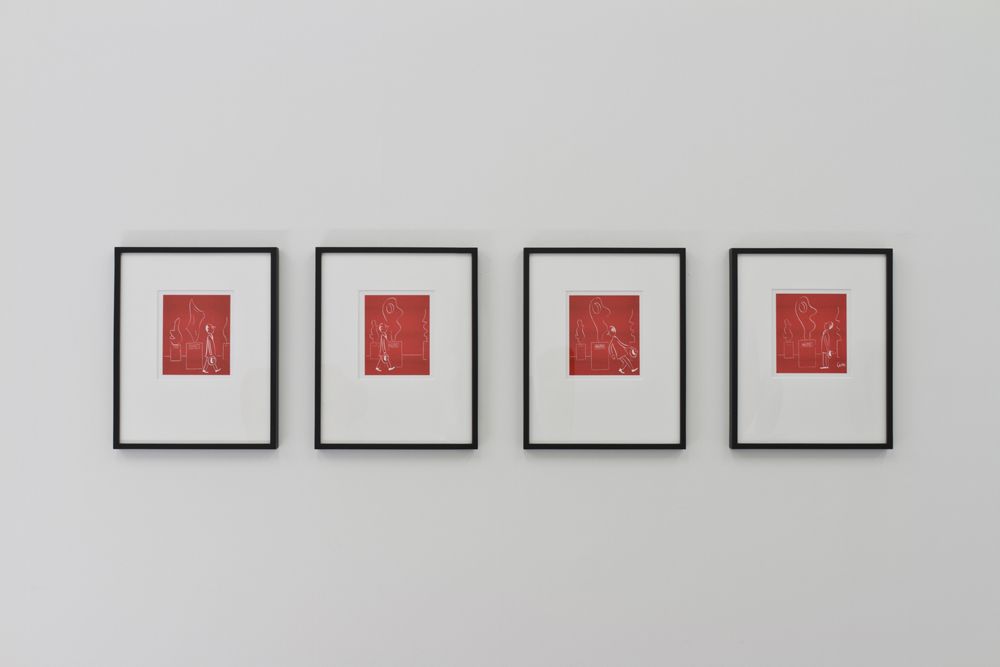

In addition to Noguchi’s biomorphic modernism, what did a “sculpture” look like in the postwar collective unconscious? Gower has made manifest in stone a group of sculptures conceived by comic artists in the 1950s and 60s. These, collectively, like a survey, portray the enduring philistinism and sexual innuendo of popular art appreciation.

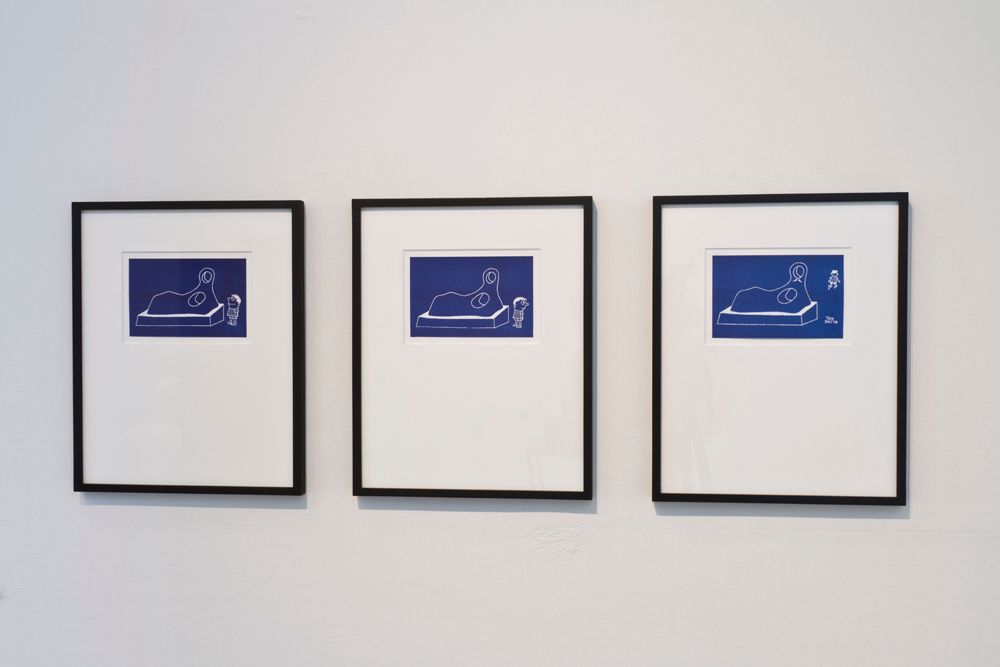

Likewise, Gower views the work of Barbara Hepworth as a signifier of modernity. In his work Display Modern (Hepworth) (2007) he asks: If you replace stone with paper—as he has done with Hepworth’s sculptures— what are the repercussions for both its cultural meaning and its psychic weight?

In his new series of paintings on photographs, Art in Latin American Architecture (2012), modern sculpture is abstracted to another dimension, painted over and reduced to a flat graphic form like Noguchi’s fragments. The difference being that here they float over the photograph’s pictorial depth.

The series Sculpture Portraits complicates the cool, clean geometry of modern sculpture. Here it is depicted in the process of being fondled and caressed by the artist. This display of neediness of the sculpture somehow undermines the heroic performance of the modern artist, and helps untether these forms from the gravitational pull of the artist’s personality. He is once again free to float peacefully into the collective unconscious.