The term Q'aqcha comes from the onomatopoeia "quach quach", which is the sound the chisel makes when it hits the rock, alluding to the first multicultural group of clandestine miners (Aimaras, Quechuas, Spaniards, mestizos, Creoles, among others) active in the colonies of New Spain in the eighteenth century. They exploited the Potosí mines without the permission of the Spanish crown, working holidays and weekends, when the official miners had to rest by order of the church. The Potosí mine, in Bolivia, was the most emblematic of the Spanish Empire for many centuries, since most of the silver exported from the Americas to Spain in the 18th century was extracted from there. It was at this time that the artistic phenomenon of the Castas paintings was enforced with the intention of classifying the presumed socio-racial groups of the Viceroyalty. Racial and cultural mixings resulting in ethnic groups, such as the Creole, lead to the discussion about what a nation really was: if a European person was born in New Spain, was he still European? And if he wasn’t, how would his privileges be justified?

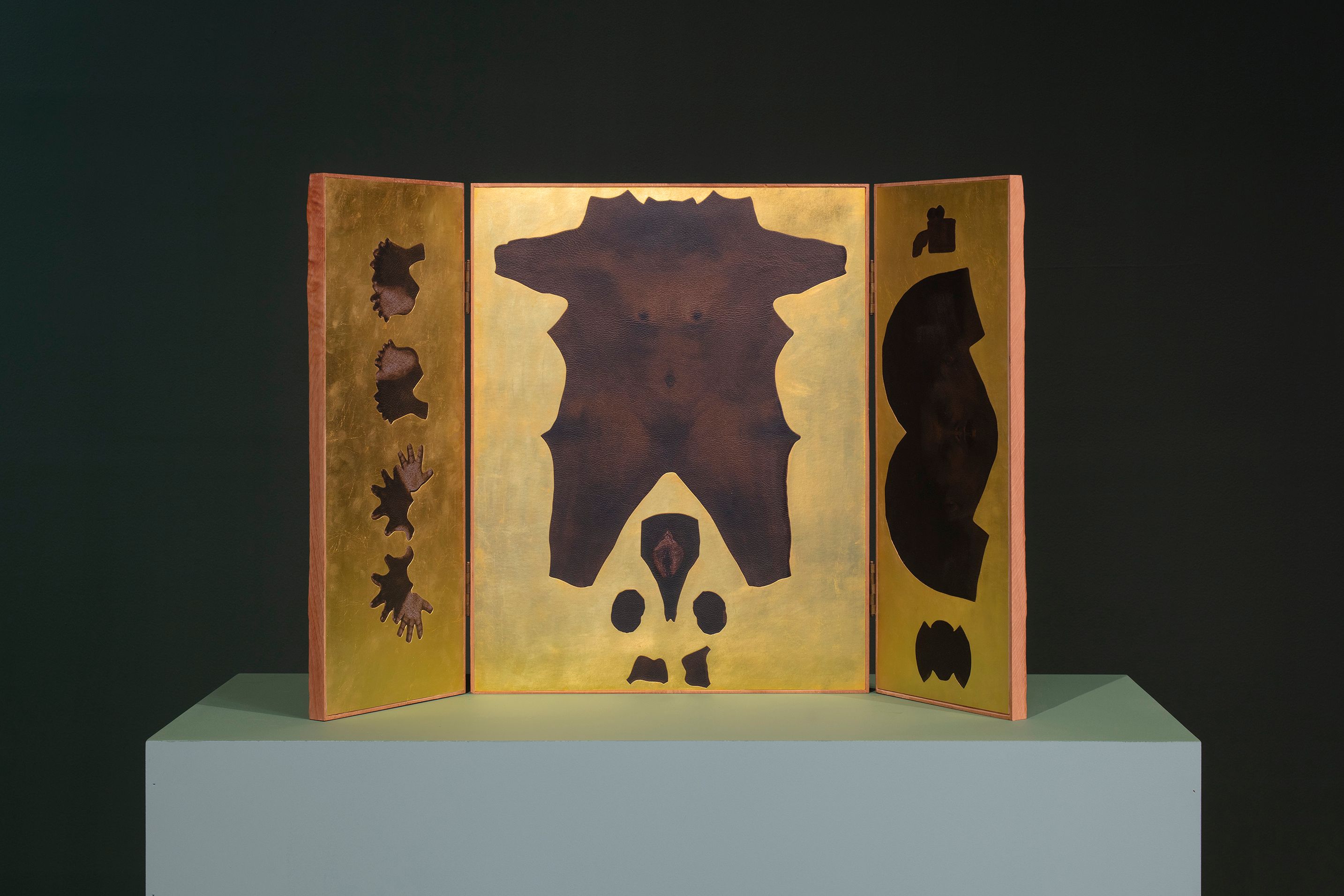

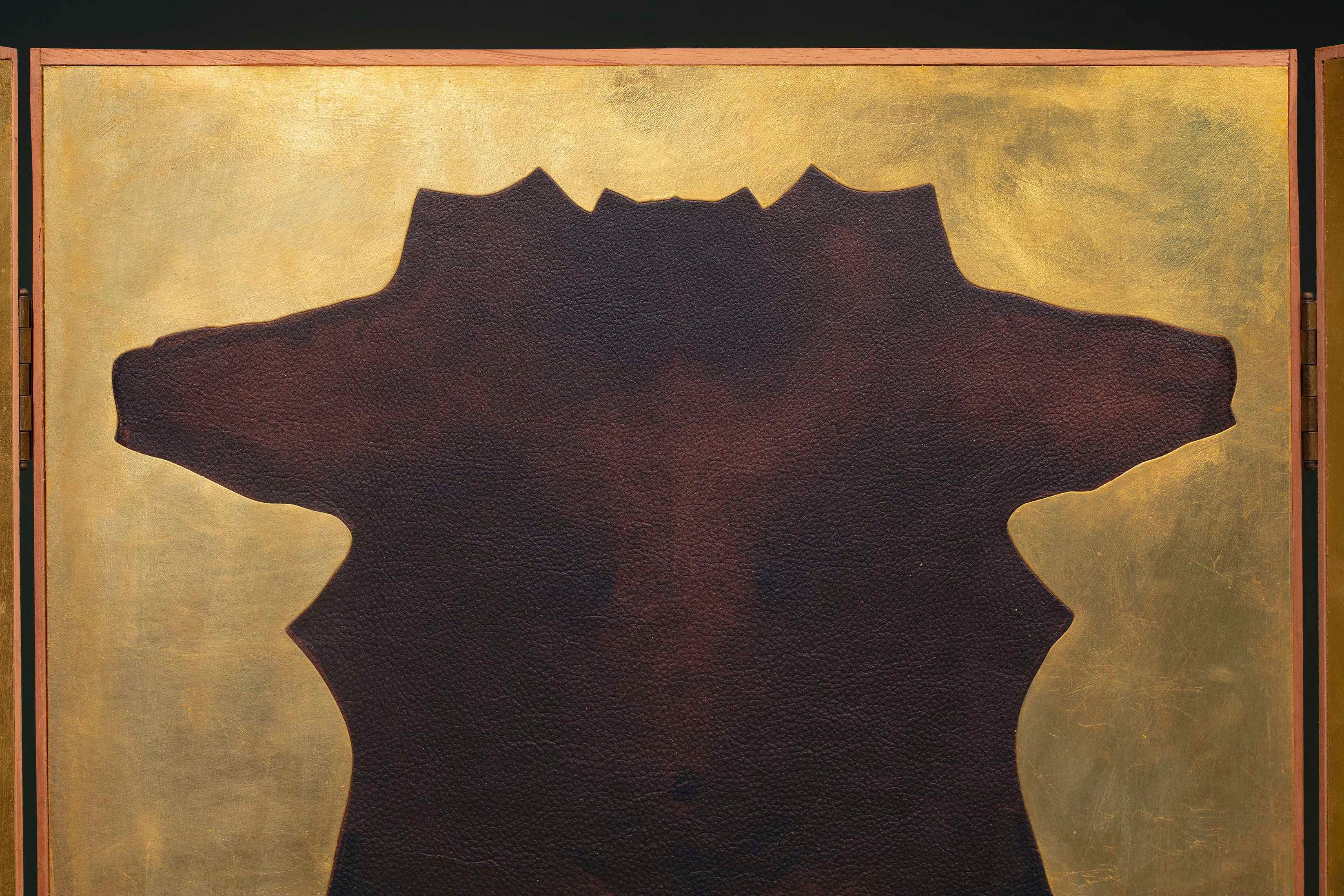

The ideological structure of the time was dictated by the church, and from there came the aesthetic of the altarpieces as a portable altar -usually displaying images of the Catholic saints and connected to the relics; objects that contained material traces and body parts that once belonged to the saints (skin, nails, bones, pieces of clothing). For this new body of work, Vega Macotela created characters by using the makehuman software, to then print their skin and features on cow leather (an animal brought from Europe). The prints were produced using steganography, a digital technique that allows information to be hidden within an image. The artist, with the help of hackers, encrypted one of the few poems that remain in Quechua - one of the indigenous languages spoken in Bolivia before the conquest, written by the Andean poet Guaman Poma.

“Cual reflejo de las aguas, eres ilusión

Cual reflejo de las linfas, eres apariencia

Al pensar en tus ojos risueños, me quedo atónito

Al pensar en tus ojos juguetones, caigo enfermo”

[As reflection on the water, you are illusion

As reflection of the lymph, you are appearance,When I think of your smiling eyes, I am in awe

When I think of your playful eyes, I fall ill]

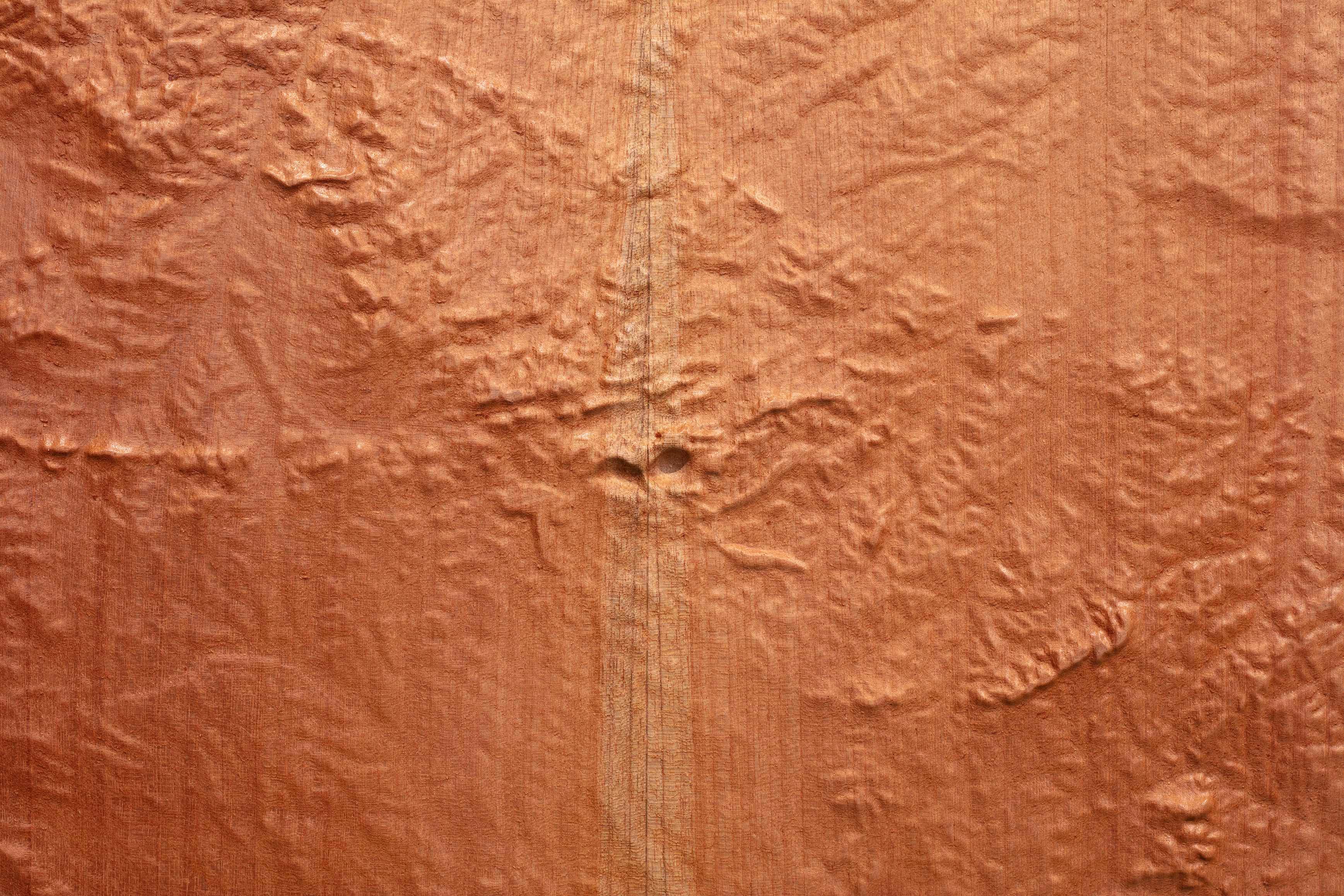

The altarpieces of Vega Macotela must be seen from the front and the back. The action of opening and closing the altarpiece is conceptually full of meaning- since, once opened, they are no longer an object, they’re an image. On the backside, we can see the depiction of landscapes on red cedar wood, where the geographical reliefs of the six most exploited mines in the world today: Uyuni, Baayan Obo, Bacadehuachi, Kalonge, Lubumbashi and Potosí. All located in Africa and Latin-America, and exploited for their minerals, which are used by the tech industry: cobalt, lithium, coltan, rare minerals, etc. This is how the “digital world” is built from physical elements which are used by some of the largest multinational corporations to build computers, batteries, screens, circuits, processors, etc. Objects though which we consume parallel digitalized realities such as apps, social networks, or even the theatrics of the metaverse.

"Es cadáver, es polvo, es sombra, es nada" [It is corpse, it is dust, it is shadow, it is nothing], will remain on view at the gallery until April, 12th.