“inalienable, imprescriptible and unseizable”¹ is the title of the first solo exhibition for conceptual artist Daniel de Paula on Mexican soil.

The exhibition derives from the need to formulate a critical reflection of coercive processes linked to the territorialization of capital in which state territorial planning and the implementation of energy generating infrastructures are intimately linked to exploitative practices and the abstract logics of property and value production.

More specifically, Daniel de Paula (Boston, 1987) conducted field research on generating systems of wind energy located in the surroundings of the city of Montezuma², from the state of Minas Gerais, Brazil, where colossal wind turbine farms stretch across the landscape in stark material contrast to the pre-existing vernacular culture.

Disguised as technical and progressive discourses that praise renewable forms of energy, such systems transform the landscape into a capitalistic force of production, obscuring the violent operations that convert communal land into a financial asset to be monopolized, commodified, and speculated upon, consolidating public and private interests and efforts in the search for profits.³

The field study carried out by the artist establishes a clear parallelism between the processes of implementing wind farms in Montezuma, Brazil with other global contexts, such as the southern Isthmus of Tehuantepec (Oaxaca) in Mexico. Despite the geographical distinctions between Mexico and Brazil, these generators similarly occupy immense territorial expansions that have serious environmental and social impacts on the local populations of mostly indigenous communities.⁴

In both cases, energy-generating wind turbines are the visible vectors of the driving forces of modernization, as sustainable development suggests a positive interpretation of energy production and, consequently, of physical and metaphysical light.⁵

However, the brilliant light of sustainable economic growth essentially constitutes the imposition of a capitalist sociability, light as colonization, light as justification for exploitation, light as aggression, and light as a productive basis of power relations. Behind the light, in the shadows cast by the wind turbines, there is a glimpse of the infrastructure companies’ imposing advancement that devastates places and people using tax exemptions and incentives to sell the ideals of progress.

In his exhibition at Labor, Daniel de Paula, by combining a variety of objects and precise gestures, continues his critical investigations of the economic and political forces that produce space and reproduce violent social relations.

In this context, from a more conceptual perspective that evidences the relationship of the gallery’s physical space with the systems of energy generation and its distribution, Daniel proposed, as part of the exhibition planning, that a Mexican collector agree to pay for the electricity of Labor’s exhibition space by selling the naming rights of the gallery’s electric bill and the light itself.

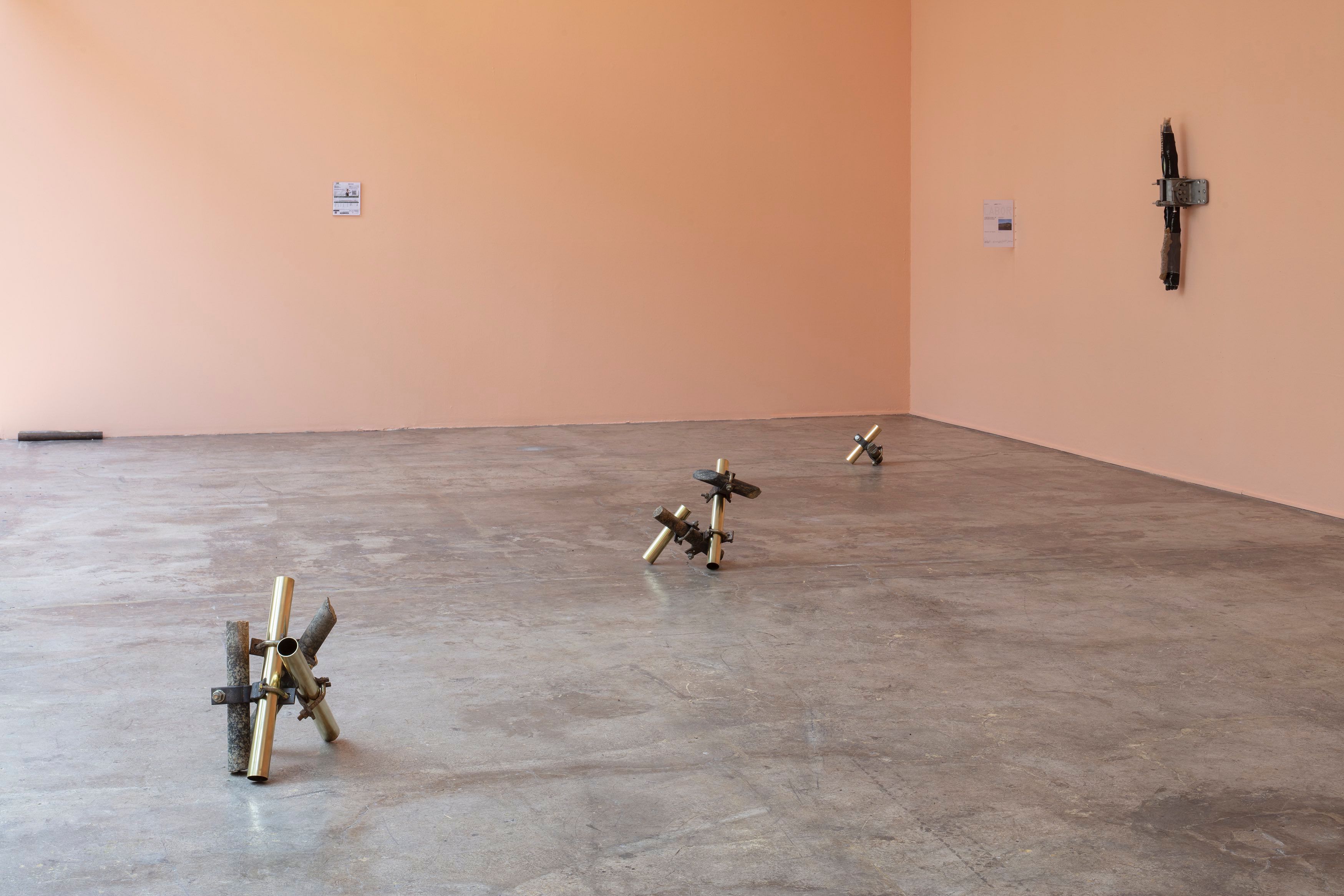

Following a logic of inquiry in the gallery space, the artist intervened the walls by mixing the paint with appropriated dust from the roads on which trucks transported the blades of wind turbines. Thus, the exhibition space emulates the real-life activities in the towns near Montezuma, where this dust settles on the vegetation in agricultural plantations preventing photosynthesis and the generation of food.

Distributed on the floor and walls of the gallery, you can see sculptures of distinctively material qualities in which the artist juxtaposes the rocks resulting from geotechnical drilling processes implemented to measure wind turbine constructions, with scaffolding clamps and brass pipes also used for the construction of power generating systems. These works are part of a sculptural series in progress since 2016, entitled inseparable spatial structure. Intermingled among them, we see another series of sculptures composed by the pairing of infrastructural cables (electrical and mechanical) with fulgurites (fossilized rays). The latter corresponds to the power-flow series, also in progress since 2020.

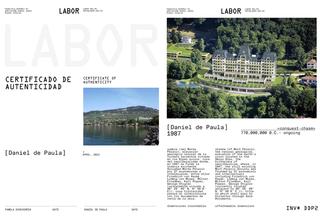

Aware of the inevitably fetishistic nature of the process for marketing his works, Daniel de Paula proposes the sale of his own shadow –through a legal contract and a certificate of authenticity– in a gesture of self-dispossession that confronts the impetuously ideological essence of capitalism, where abstract concepts of property, value, capital, and labor advance above all else as a solid penumbra.

In addition to this work, and using the same contractual procedure, Daniel proposes the commercialization of shadows belonging to three mountains related to the history and formation of neoliberal ideas in the world, confronting the materiality of geology with the intangibility of capital.

Finally, in a video presented from the artist’s own cell phone, Daniel compiled ghostly images resulting from his field research in the surrounding Montezuma area.

The exhibition inalienable, imprescriptible and unseizable is not only interested in the residue that emerges from the objects of the artist’s study –in this case, the wind farms in Montezuma–but also, in the professional context of art. Despite the positive feeling of autonomy linked to the artistic field –separated in appearance from the world crisis– the art market reproduces, in its essence, the shadows of capital and its dominant social relations.