An art gallery is often a misunderstood enterprise. From the outside, it may seem like a utopia of sorts: a place where like-minded outcasts can frolic and experience true freedom, where artists and collectors share cocktails while discussing the latest fashion trends, all the while the world all around them ignites in a fierce fire. But for those of us who inhabit the art gallery in a more or less quotidian manner, this seems like an absurd, oversimplified fantasy that ignores the material realities and social dynamics at play. In fact, an art gallery (and a contemporary one at that) is a place of business, where a group of people works toward a common purpose, one which ideally operates within a fertile economic structure that paradoxically isn’t trying to achieve financial excess, but to utilize whatever currency it amasses to continually promote artistic practice. Perhaps we call it practice because it’s a venture where we can constantly get better, knowing all the while that perfection –like a utopia– will never be achieved.

The case of Labor is a particular one, not just because of the name, which implies and inherently operates as a concept that suggests an observation of specific political fluctuations, situational economic flows, or case studies of social action. In certain academic circles, the construct of Utopia is often a tool to inspire people to enact practical changes that might seem far-fetched or presently out of reach. Some artists working with research-based practices choose (or perhaps adhere to) a livelihood that depends on challenging normative situations through processes of creative speculation by offering glimpses into the very alternatives that lie beyond them. Labor is a gallery whose inception exemplifies these sorts of artistic ambitions by providing not only a playground for ideas to be contested, but a platform to celebrate their construction and debate on their individuations.

The definition of the word labor carries some specific connotations, a few of which are already well defined by left-leaning Marxist academics, often superficially understood, and decoded as a semiotic mechanism that explains why there is a value in art and how it can become an object of luxury. These objects, or materials, are what constructs, explains, and ultimately defines what a diminutive group of people could agree is or is not a work of contemporary art. What, then, constitutes artistic labor? Is it the outcome of creative genius riddled with the suffering and heartache of a tortured individual? Or could it be better to choose not to define it categorically, leaving it to be or not be something else?

The present exhibition is titled “Bread & Roses,” referencing Rose Schneiderman’s 1912 speech in a campaign for women’s suffrage (the right for women to vote). Where she stated her right to go beyond work, but to live, and to enjoy it. For the 15 years of Labor, we aim to posit this same sentiment, albeit more than 100 years later, and through the lens of artworks that have been created in an age of looming disaster, chaos, and political turmoil. As absurd as it may seem, the show is simultaneously an example of Schneiderman’s argument but also an example of it operating in practice: the exhibition is ultimately a celebration.

Inside the gallery, absurdity is more than present, perhaps no more succinctly than with Raphael Montañez Ortiz’s “Piano Destruction Concert: Dada con Mama,” which reminds the viewer of the 2014 action carried out by Montañez at Labor. The gesture of disfigurement is one of the artist’s most consistent recurring motifs, which “utilizes the destructive processes to purge, for as it gives to death so that it will give to life.” The remnants of the piano can hint towards something simple yet deceivingly complex, on par with the Dadaist tradition of the recontextualizing of everyday objects. Montañez steps beyond the ready-made by considering uselessness and speaking towards the paradox of practicality – the double-edged nature of intellectual speculation – something paramount about the empirical implications of destruction. If destruction in the art gallery may prompt a conversation, what could a decay of social order on a massive scale?

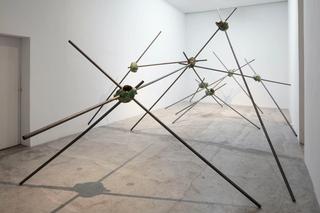

Jorge Satorre’s half-buried, though still visible structure, accompanied by drawings and other smaller sculptures, is an example of a trace that posits similar predicaments. Produced for his 2017 solo show at Labor, “Un tema moral moderno, decorar el agujero,” the original iteration of this piece functioned as a reminder that the gallery used to be something different and that, like many artistic spaces, the practicality of the architecture might have been more tacit in the past. Satorre’s piece proposes an empirical analysis of how exactly the space changed and questions if the shift from a residence into an art gallery is an evolution. Like Henri LeFebvre, who rejected the asceticism of modernist architecture, calling it “bourgeoise morality”, so too, does Satorre critique the literal structure of the contemporary art gallery.

Not far from Satorre’s gesture, the departure point for Etienne Chambaud’s “Fractal Zoo” gives us a metaphysical analysis of the very process of creation of figures that we inherited from modern machines – such as the zoo and the museum. Like many other of his deceivingly complex projects, Chambaud’s “Fractal Zoo”, navigates the idiosyncratic by turning it on its head, in this case even during the production of the piece, which involved having live birds defecating on the artwork, and all over the gallery.

Also referencing, or appropriating the natural world, is Pablo Varga’s Lugo’s “Cenote”, where the public encounters two cavities: one in the ceiling of the space, which facilitates the light from the outside to seep in, and another in the ground. Here, the exhibition starts to make apparent the connections beyond Western philosophy and architecture, towards the esoteric (at least for us Westerners) theologies which Vargas Lugo and Montañez Ortiz consistently rely on. Noticing the metal sieve on the ground, which partially covers the hole, a viewer can appreciate the design of a Tibetan mandala, which signifies the aspiration towards illumination, and unity of consciousness. The narrative of the show thus attains a dimension that transcends a mere critique of Western thought, by positing an alternative in the cultures that are often underrepresented in contemporary art and by providing a temporal splice towards ancient cultures such as that of the Mayan People and the Tibetan Buddhists.

Present-day vernacular is also present within the space, in Héctor Zamora’s “Protogeometrías 11 & 18”, and in Pedro Reyes’ “Disarm Music Boxes (Karabiner/Matter)”, and “(Beretta/Vivaldi).” The former is in the shape of tricycles holding lattice structures made of terracotta, and the latter with two music boxes built with repurposed rifles. In both cases, a game is being played with elemental compositions that have been radically recontextualized to achieve new objects through physical reconstruction. Ethical imperatives are questioned through these artworks by bringing problematics of macro-social scale with questions such as: what can be a poetic way to utilize a weapon, or, what if a fully mounted construction were to be transported through the streets in a tricycle?

What if might be one of the central principles that drive, but also have defined Labor’s fifteen years of existence, a central narrative thread that connects the work that we aim to present to the public through a series of experiments which some might call social, others semiotic and some even aggressive. Challenging the social order by pondering the limits of language is what Erick Beltrán’s “Nothing but the Truth,” the group of works located at the entrance of the gallery, aims to do. For this project, the artist used a printing press in which the public was asked to write their favorite lies. Now, visitors are greeted -or confronted- in the gallery with some fragments of this project, labeled with acrylic paint on cotton canvas.

But there is another textile in the exhibition, also presented on a large scale in the form of a tapestry: “Burning Landscape VI,” by Antonio Vega Macotela, evokes the way in which invisible flows of data, capital, and other virtual operations that corporations often profit from, can have a visible impact on the landscape. The piece is part of the project “Incendio” [Fire], a project in which the artist resorted to steganography (a method allowing to hide data in plain sight) to encrypt the more than 2000 names of tax evaders contained in the Lagarde list, showcasing the relationship between hidden corporate interests and the increasing number of natural tragedies in the world.

While some works in the exhibition explore economic, climatic, and social concerns, others look to art history and the intricate references that fabricate our collective understanding of beauty. Such is the case of Terence Gower's “Free Association” mobile, whose pieces hang dispersedly from the ceiling assembled in a corner of the main exhibition space. If read as a cartographic constellation, these abstractions clearly reference motifs from Isamu Noguchi's work of the 1940s. The aptly titled “Free Association” evokes not only an aesthetic stimulus but also an emotional one: here, abstraction offers the public a series of possibilities for recalling history and rethinking the relationship between the contemporary and the modern.

Placed on a wall below Gower's work, a screen loops two videos by the artist Jan Peter Hammer. The pieces are in chronological order, starting with “The Anarchist Banker” followed by “Monarchs and Men.” These works document both fact and fiction; utilizing documentarian-like methodologies, to achieve a form of defamiliarization. The central figure of both pieces is a character (quite literally an anarchist banker) who is also a reputable art collector. Treated as a case study, Hammer places this oxymoronic figure as an example of how the art market and the gallery space may often appear obscure, sometimes in unintelligible ways, when encountered by those who are new to the art world.

The hermeneutic study of the past century, as well as the aforementioned critique of modernism, both in art and architecture, arise yet again through complex social dynamics with Jill Magid’s subtle neon gesture entitled “Barragan®.” Nestled cozily atop a bench outside the white cube. This artwork is part of Magid’s research project: “The Proposal,” – which involved researching the legacy of Luis Barragán and contesting the copyright to his designs, which are still owned by the Swiss company Vitra. The exhaustive multifaceted process that took Magid several years became public and quickly became the subject of major controversy, a topic of international discussion, and even the thematic case study for several research papers. Especially due to the ultimate result: a diamond ring made from the ashes of the late architect. Whether or not one agrees with the decisions taken by Magid to bring this project to fruition, there is no room for doubt when considering the piece’s tantamount relevance.

After fifteen years in the making, we ask: what, after all, is a celebration? And how can it function as something distinct from the usual? If Labor’s trajectory has been nothing short of unconventional, it makes sense that its commemoration should acknowledge that. To conform is to succumb to mediocrity, to obliterate the unique sparks that distinguish the remarkable from the mundane. It may be curious that one may find a sense of truth in oddity—unapologetic, unrestrained, and undeniable. Daring to change pace, to stop and to observe, to embrace and to think

before continuing in motion.