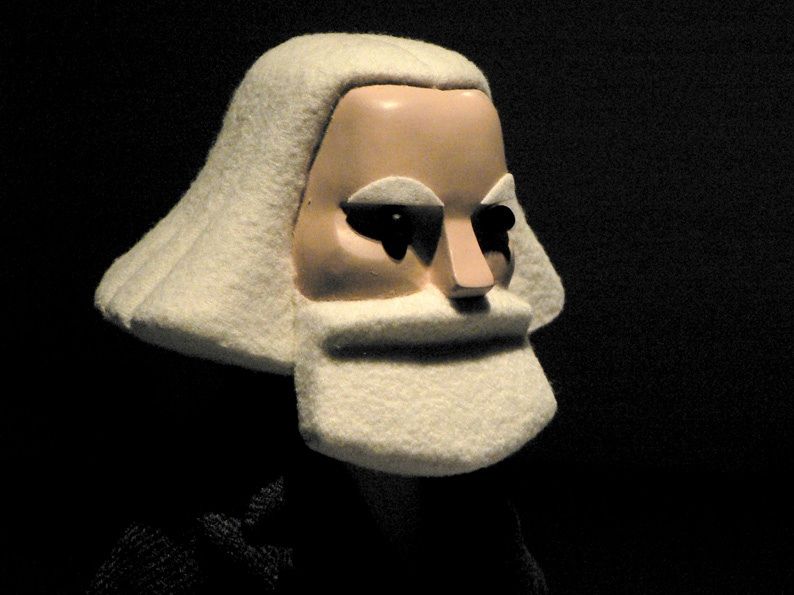

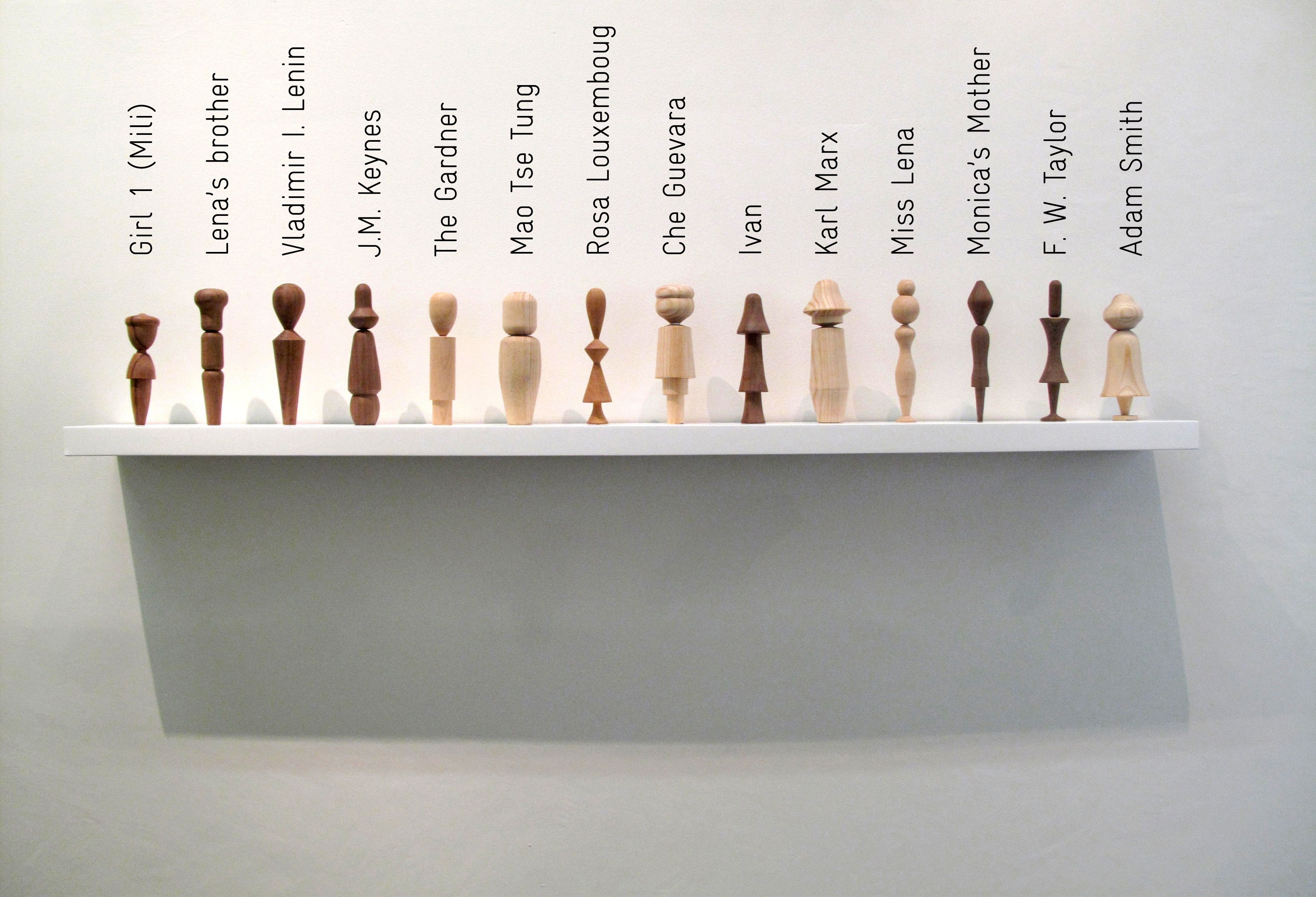

Reporting on the advent of the Second French Empire in 1851, Marx famously repeated an insight he had read in a letter from Engels, itself a variation on Hegel: if all great world-historical facts and personages occur twice, the first time they do so as "grand tragedy," the second as "rotten farce." A century and a half ago, Marx and Engels regarded this repetition with despair, brandishing the category of farce as a denunciation of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte's dictatorship. In the context of advanced capitalism, however, Pedro Reyes (Mexico City, 1972) asks us, with Baby Marx, to re- evaluate the political inheritance of both repetition and farce.

Taking up a recent trend in the production of Hollywood blockbusters, Reyes proposes to "reboot" the nineteenth century debate between socialism and capitalism. Media moguls such as Ronald D. Moore (Battlestar Galactica) and J.J. Abrams (Star Trek) have similarly resurrected dystopian, Cold War-era visions of the future to great commercial success. Repetition recommends itself in these latter contexts principally as a means of streamlining the production process itself: brand recognition has been subsidized in advance, capitalizing on consumers' prior emotional investments in the franchise's narrative. Conjuring the specter of Marx with the assistance of a film production company, by contrast, Reyes asks whether the iterative logic of franchising might not be twisted away from the rationalized production of surplus value, and whether, consequently, the utopian dreams of Marx and his puppet allies might not discover a renewed vitality in the Crisisville Public Library. Of course, franchising Marx's thought has always been tricky business, as the demonic figure of Stalin reminds us. The unfinished narrative of Baby Marx leaves us with the open question of how capitalism's own strategies might be used to reanimate a post-Soviet socialist project.

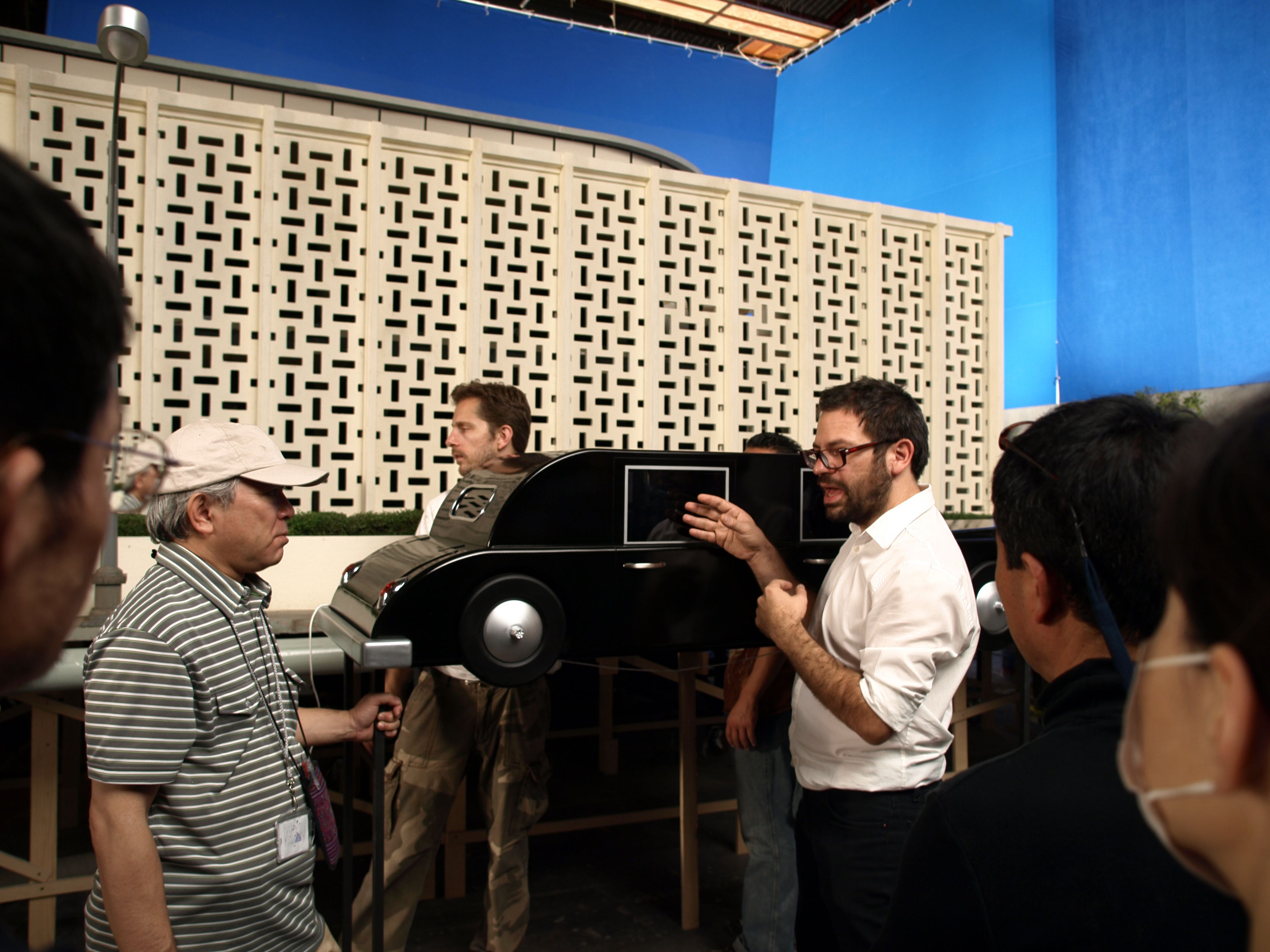

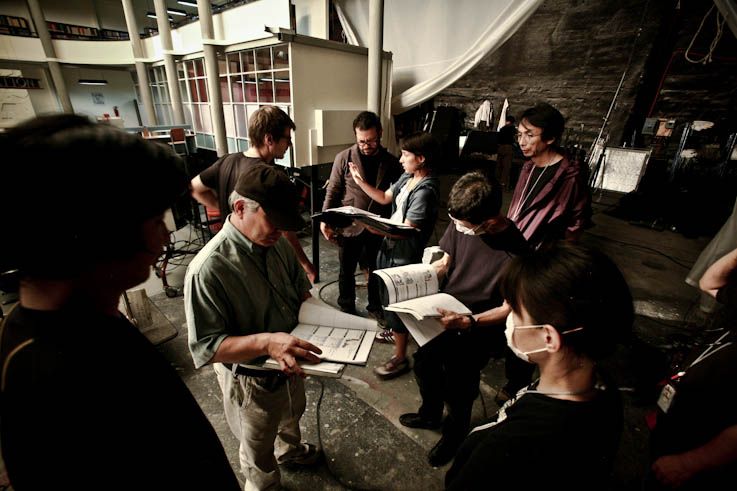

The structure of repetition spills out from within the timeline of Baby Marx into the space of exhibition, confusing any rigorous distinction between surface and depth. Redeploying a marketing practice that has become de rigeur since digital video discs deposed VHS tapes from the throne of the mass market, Reyes gives us access to "The Making Of" Baby Marx as well as rushes from the filming of the pilot episode. Even prior to farce's repetition, then, rehearsal has already congealed into a potential source of value. Spatializing these by-products of his own televisual commodity within the gallery, Reyes posits an object lesson in the alienating force of capitalism: beneath the surface of this particular commodity fetish we bear witness to a team of puppeteers huddled together, laboring under the direction of the artist-manager. The flat surface of the television screen gives way to three-dimensional space, and we are invited to inspect the Crisisville Public Library not only as a sculptural curiosity, but also as a stage, a factory, the scene of a crime.